IMPERIAL EYE

A collector of 20th-century Russian art is so intrigued he makes it his business.

Art & Antiques Collector's Sourcebook - Winter 2008

Writer: Christopher Hann

Photographer: John M. Hall

James Yarosh can trace the change in his artistic direction to the day in 1994 when he glimpsed a crimson-hued abstract painting titled “Angel” by Russian artist Andrey Skripka. Yarosh had immersed himself in art his entire life and was just starting a career as a painter – a struggling painter, perhaps, but a painter nonetheless. Then came “Angel.” The work knocked Yarosh for a loop. Like most Western artists, dealers and collectors, he knew little about the vast body of work produced throughout the Soviet republics from the early 1930s to the early 1990s.

Yarosh was just 29 when, in 1997, he opened his own gallery in Holmdel, New Jersey, a well-to-do suburb about an hour’s drive from New York City. As a gallery owner, Yarosh scrutinized the art world with new eyes. “Part of my role as an art dealer,” he says, “is to reinvent the wheel.”

Before long, Yarosh encountered the surrealist paintings of another Russian artist, Vachagan Narazyan, who populated his wispy, dreamlike scenes with images of children and circus figures. Inspired by Narazyan and Skripka, and thirsty for more, Yarosh began to explore the work of Soviet-era and Russian artists, who had spent most of the 20th century toiling outside the realm of international influence or attention. “Being an artist, seeing what they were doing, it was just so humbling and amazing,” Yarosh says. From a self-directed crash course he discovered that for 60 years, from Stalin to Gorbachev, art was used as a Communist tool and artists were forbidden to stray from the government-prescribed style known as socialist realism. He learned that Skripka and Narazyan were among legions of Soviet artists who worked in opposition to party policy to produce an underground network of so-called nonconformist art. And he learned that the Janes Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University in nearby New Brunswick , New Jersey , contained the world’s largest collection of nonconformist Soviet art, the 17,000-piece Nancy and Norton Dodge Collection.

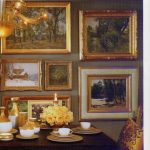

Today the works of Soviet-era artists and their cultural descendents—traditionalists and nonconformists alike—dominate Yarosh’s personal collection as well as his gallery inventory. In just 10 years he has amassed works by some of the former Soviet Union ’s most eminent artists. On a single wall of his lavishly appointed townhouse on the Jersey Shore hang works by traditionally trained artists such as 90-year-old genra painter Yuri Kugach, the patriarch of an artistic family considered the Wyeths of Russia; his wife, Olga Svetlechnaya (1915-97), whom Kugach met around 1936 when both were students at the prestigious school known today as the Surikov Moscow Art Institute; and Vyacheslav Zabelin (1935-2001), the legendary landscape painter considered the father of 20th-centruy Russian Impressionism.

An opposite wall contains about a dozen paintings and drawings by Narazyan, including a 60-by-60-inch diptych that features the artist’s trademark elfin figures dressed in circus tights, wielding bows and arrows against symbols of the Soviet government. Of Narazyan’s works, Yarosh says, “They have sort of a whimsical as well as a dark quality to them.” The painting’s placement—above the statuary English fireplace—represents its standing in the Yarosh collection.

The work produced by the artists in what is known today as the Moscow School of Russian Realism ranged from blatant propaganda to pure poetry. In the 1950s even Kugach painted images that glorified the Communist regime—one was titled “Praised be the Great Stalin”—though he is better known for the technical brilliance of his landscapes. Yet Yarosh says even the party-line images—the humble peasants happily at work, the idyllic grandeur of the Soviet countryside—reflect a mastery of light and form. “The Energy of the Clouds,” an 8-by-8-inch painting of a sunset by Nikita Fedosov (1939-92), captures what Yarosh calls “that perfect moment in light.” Among the highlights if the Yarosh collection is Kugach’s lush, impressionistic “Lilacs.” Yarosh says the artist’s son, Mikhail, considers the work his father’s finest landscape. “It was really the coloring, the styling that was Russian—the warm sun and the cool shadow,” Yarosh says. “The color relationships made it intrinsically Russian, but the subject matter was universal.”

The three-story townhouse that Yarosh shares with Barney Cohn, his partner of 15 years, is set into a steep hill in the seaside village of Highlands . The home overlooks the aptly named Sandy Hook, a narrow, 7-mile stretch of beach at the northern tip of the Jersey Shore . From Yarosh’s third-floor balcony, the view extends east to the Atlantic Ocean, just a few hundred yards away, and north beyond Raritan Bay and the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge to the southern tip of Manhattan , some 20 miles distant. Two years ago Yarosh oversaw an extensive home renovation that enabled him to transform his residence into a more fitting showcase for the art. In the living room, twin Lalique chandeliers, circa 1930, were imported from France . They are framed by mahogany ceiling medallions hand-carved in a starburst design by Marcelo Barvaro, who also makes many of the elaborately etched frames of Yarosh’s paintings.

In assembling works for his own collection as well as his gallery, Yarosh has teamed with John and Kathy Wurdeman, owners of Lazare Gallery in Charles City, Virginia. Since their first meeting at a New York show in 1999, Yarosh has come to regard John as the most important dealer of Russian art in America . (Wurdeman’s 32-year-old son, also named John, is the only American artist to attend the Surikov Institute in Moscow , where he was taught by Zabelin.) Of Yarosh’s home collection, Wurdeman says, “Most of these artists that he has have 50 to 250 paintings in museums, primarily in the former Soviet Union . He can recognize subtle nuance that escapes most people. Few people, even in the business, have a really refined eye. James has such an eye.”

His timing is not bad, either. In the 10 years since Yarosh opened his gallery—the past two years in particular—interest in Soviet and Russian art among American collectors has risen sharply. Prices have followed. Narazyan’s finest works have quadrupled in value in the past decade, Yarosh says, to $30,000. Zabelin’s top paintings sell these days for more than $150,000. “Lots of art that has never been accessible before is now being seen by the wider public,” he says. “That’s why this is such an exciting time for Russian art.”