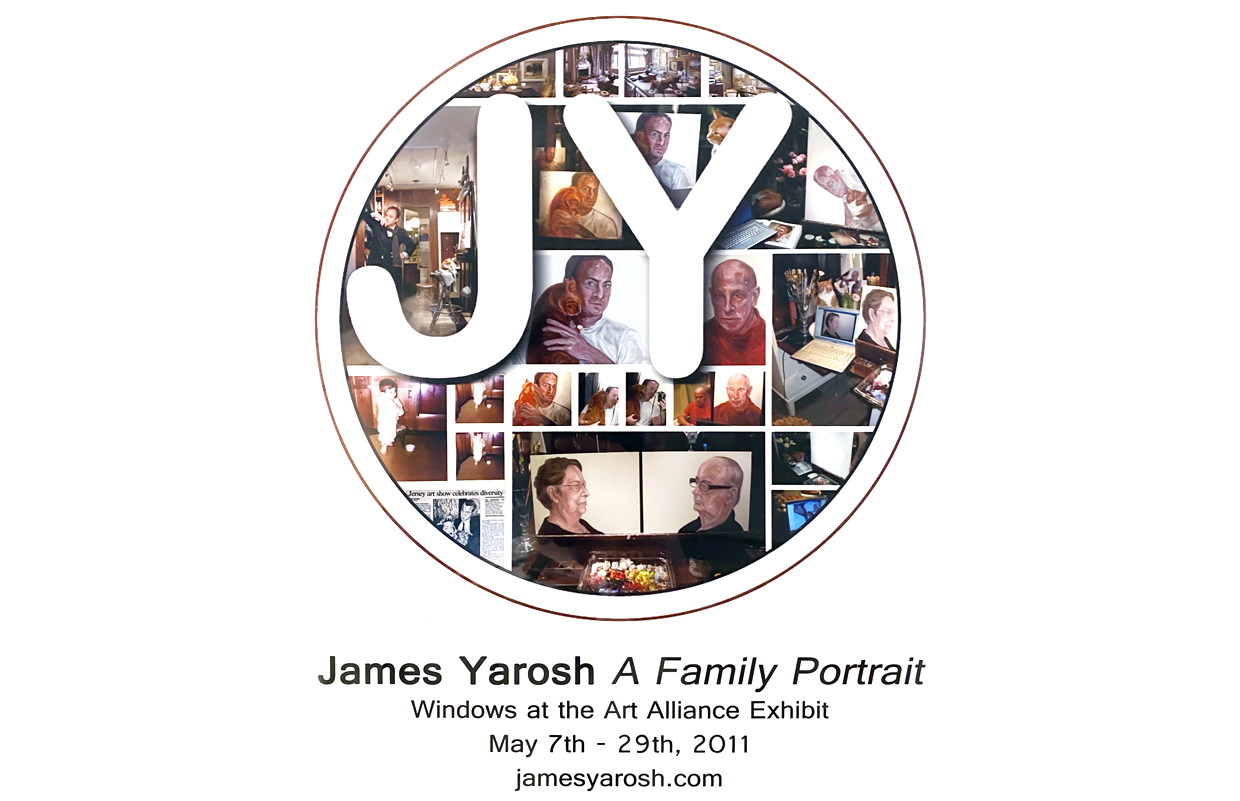

James Yarosh Paints His Loved Ones

Better known as a dealer of contemporary Russian art, James Yarosh returned to the easel in 2007 and is now exhibiting several of the resultant oil paintings as A Family Portrait. On view May 4-29 at the Art Alliance Artist Co-op Gallery in Red Bank, NJ, these canvases form a complex self-portrait of Yarosh himself, seen through the lens of how he views his loved ones. Although the works are not for sale, they are well worth seeing.

James Yarosh is an artist keenly aware of how the tendrils of intimate and familial relationships intertwine to create the person each of us are at this moment. In the decade since he opened his eponymous fine-art gallery specializing in contemporary Russian art, Yarosh, who previously was known for painting bold abstracts, has put his own art on hold, opting to absorb the Russian tradition and conventions of the artists he represented. But as he grew his business, he turned around 15 years later to see life has changed for his parents to weather the changes that life inevitably brings and what that means to himself as a son resulting in a refocus of the importance of “moments” and not missing any future with his partner, Barney.

In 2007, Yarosh decided it was time to return to the easel. “A Family Portrait,” the resulting series of oils on canvas is part character-study, part love-story; collectively, they form a complex self-portrait of Yarosh, as seen through the lens of how he views his relationships with those he holds most dear. The fact that Yarosh returned to painting at 41 is significant to the artist, who eyes life’s milemarkers as pivots guiding his career. “We each have different goals to achieve in each decade,” he explains. “I worked very hard in my thirties to be a business success. In my forties, the idea is to conduct myself as a businessperson on my own terms. This series is a way for me to go back to being an artist.”

The paintings were informed by Yarosh’s collaboration with the Russian artists he represented — “I admire their discipline, the conviction, the love of art, how it is really pure,” he says — and from recent visits to European museums, where he studied the portraiture of Oskar Kokoschka, Egon Schiele, Lucian Freud, Velázquez, and Goya. The initial canvas in the series, a self-study of Yarosh and his beloved tomcat Ilean, echoes his admiration of Kokoschka and Schiele’s self-portraits. “I had an empathy, felt a connection,” Yarosh explains. Schiele’s Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern (1912) is evident here, in Yarosh’s selection of a semi-profile, chin-to-shoulder composition, with the nuzzling Ilene placed where the Chinese lanterns hang in Schiele’s work. The fluidness with which the former stray, who Yarosh and Barney nurtured into domesticity, swoops into Yarosh’s torso is a poignant key to the rest of his series, which showcases the balance of trust and vulnerability that is present in every human relationship and in the dynamics between artist and live subject.

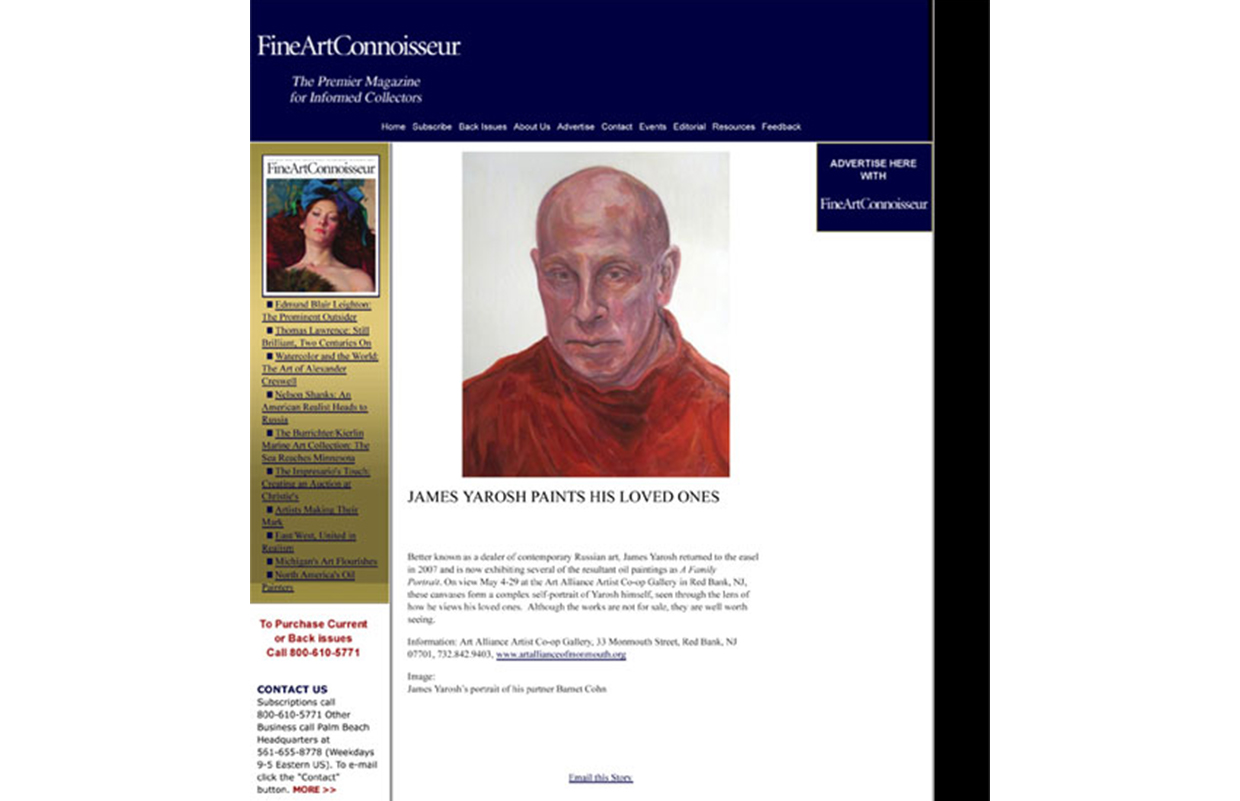

As with his pet, Yarosh explores the nuances of the connections he has with those he loves — and who love him — in his subsequent works. “Barnet Cohn,” the unsentimental portrait of his boyfriend of 18 years, was not meant to be a set with Yarosh’s self-portrait, but was painted in a way that they would work together. “We’re both so opposite, and he’s such an individual,” Yarosh explains. “That’s what works so well with our relationship — the opposites.” Contrasting with Yarosh’s affectionate self-portrayal, which engages the viewer in a playful way, “Barney” stares off, pensive, brooding, not at but just past the viewer. “It’s a mug shot; he has no vanity, no airs,” Yarosh says of his partner, who held the highest-ranking uniformed position in the New Jersey prison system retiring after three decades of state service in 1996. “He’s very singular-minded. He’s determined to forge out this life he wants for himself. There’s an intensity to him; he’s not looking to engage, except for those who love him, for them he’s endearingly funny and very cool to know.”

In keeping with his new mode of subtle sophistication, Yarosh cast the thoughtful “Barney” with orange accents, less a commentary on his partner’s disposition than a nod to the freckled redhead Barney grew from. The saturation of ruddy layers is in stark contrast to Yarosh’s self-portrait, which, while fierier in attitude, is demurely rendered in its white-on-white tones. To those who know Yarosh, the dealer with fashion flair, the portrait is a window into his private life. “The white tee shirt seemed very simple to me, and with me being a clothes horse, it shows how clothes really don’t mean anything to me other than the novelty of dress,” he explains. “I arm myself with my wardrobe for work, but it’s not what’s real to me. It’s me not needing to be bold, but a content to be more quiet.”

Having Barney, and then subsequently his parents, pose live for him for up to seven sittings was a way for Yarosh to arrest time, stop the aging for those he loves most, and preserve the memory of that moment. “My partner is 13 years my senior,” he says. “He had valve replacement surgery about 12 years ago, and I was concerned that I might lose him. When Barney sat for me, I did not put my feelings on him; I was recording him, trying to get out whatever he was giving. My boyfriend and parents are shown with all the complications of what I bring to them; all the love and hurt that are in my mind are in these paintings.”

Rendered in almost-profiles, Yarosh painted his parents as a two-canvas set, facing each other, and represented with a relaxed, non-nonsense demeanor. “My parents are the unit, the team,” the artist explains. “I wanted to make them very human, with all the psychological complications.”

As with Barney, the hours spent sittings with his parents was very precious to Yarosh, who lives a distance from them. In their portraits, he shows the unconditional love that a child has for a parent. “Painting family is a loving thing to do,” he says. “I wanted to represent their history, but also show empathy for the story of their lives.” The quiet visage of his father depicts the man Yarosh knew growing up with very little in common with other than our own convictions of right and wrong. “He very much lived the classic father role: He was the breadwinner, we went fishing, we worked on cars,” Yarosh says. “He also was involved in the church, sang in the choir, and was a Eucharistic minister.”

His mother is rendered with a strong countenance, perhaps as a nod to how she served as a champion for Yarosh as he was growing up. “You can see the love in her eyes and a little bit of a smile that is reassuring to a child,” he says of the work. Her skin bares the ultra-feminine tone of rose-petal pink, a reflection of a woman who always lived her life with class. “But,” Yarosh is quick to note, “There’s also a formidable woman there; a mix of power and sensitivity.” Layers of family history are implicit in his mother’s jewelry: The heirloom marcasite and pearl necklace that encircles her neck had been given to James’ grandmother from his grandfather when they were first dating. “The pearl earrings are classic, and say a lot about her,” Yarosh says. “My love of traditions and even holiday menus learned by cooking together growing up from family recipes I owe to my mother.”

After the show closes, Yarosh will keep the paintings. “I did them for myself. I have young parents — they are only 20 some years older than me — but with all the worries, they are giving me the gray hairs now. I see their frailty and have more empathy for them than see them as parental icons. They are people making the most of the rest of their lives, but I see the signs of fear that I somehow wish I could take away.

“These portraits are a way to immortalize my family,” he continues, “and by painting them I’m recreating them on my own terms. I am the youngest in my family, and if I end up being the last one standing, I’ll still have their presence around me.”

James Yarosh, “A Family Portrait,” can be seen May 4–29 at The Art Alliance Artist Co-op Gallery, 33 Monmouth St., Red Bank.

As the show house preparations progressed and she supported James in his project, Regina received a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer that she chose to keep secret until after her son’s work was complete and the house open to the public for view. James recalls this as a most loving act by his mother. He dedicated the room to Regina with gratitude for her caring words of encouragement: “You know you can do this ... you only doubt yourself when you are tired ... and for then I am here to remind you.”

The coming year saw James with a heightened focus on family while still balancing the demands of the gallery. All the while, Regina cheered him on and gently reminded him to take time for himself, too. Regina passed on December 7, 2014, a day before James was to begin a new course of painting studies in Manhattan. Plans were cancelled.

Work, however, had sprung into high gear on the heels of successful fine art and design presentations that increased the gallery’s reputation. James immersed himself into his career again, creating interior design projects that showcased beauty and set the stage for future happy life scenarios to play out. The path was an easier one than facing the loss of family and facing a blank canvas on an easel..

But family remained at the forefront. On August 9, 2016 — James’ birthday — he and Barney were privately wed at the Atlantic Highlands Courthouse, with the mayor officiating and two dear friends serving as witnesses. Then on August 19, on the occasion of the couple’s 23rd anniversary, they were more formally married and took a wedding portrait.