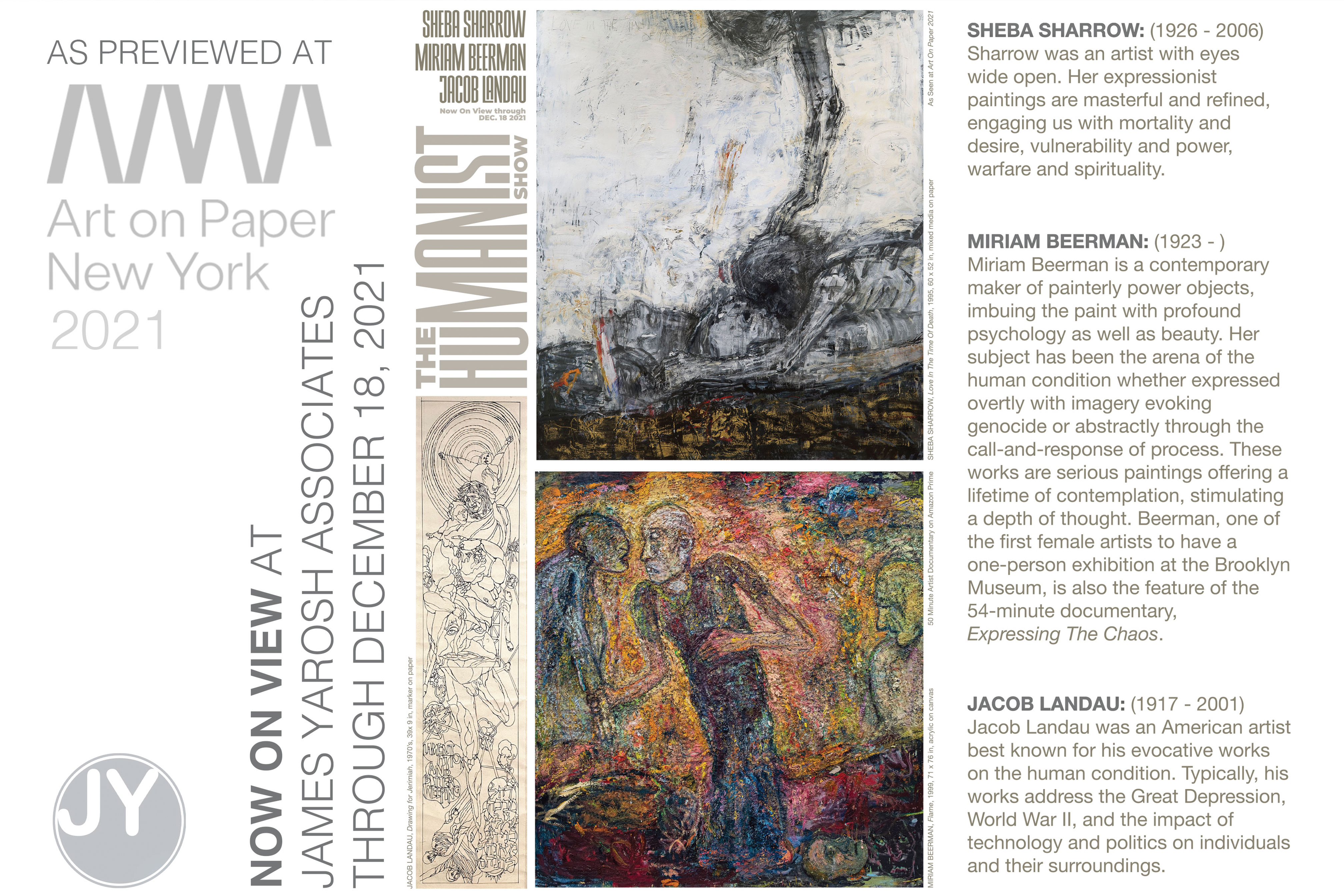

SHEBA SHARROW, Involute, 1999, 72 x 84 inches, Mixed Media on Arches Paper

Sheba Sharrow’s painting INVOLUTE – A gallerist’s shared fine art conversation

With my gallery’s participation in the art fair ART ON PAPER 2021 as part of Armory Show Week in New York City, I must admit I was craving the idea of talking about art. I missed having my audio tour teachers at museums both locally and abroad during last year’s shutdown. I wanted to create conversations that stem from the art and to share how the pieces can connect us and become healing and nourishing for our souls—in the way that only art can.

I started the idea with the solo presentation of expressionist and humanist artist Sheba Sharrow, a powerful talent, the undiluted voice of an activist painter whose work I believed important and worth talking about. Her works also were ones that create the type of conversations I relish hearing about myself when I discover the secrets behind paintings. I have been proudly advocating Sharrow’s work at my gallery since 2007. To help open conversations, I began by printing the following words on the walls to set the tone that our goals were bigger than what was within our 12 x 12 space:

Sheba Sharrow (1926–2006): Sharrow’s expressionism is direct, using both force and tenderness. The lyrical line of her hand becomes a visual poetry. Her art has an elegance, embracing formal balances of good to overcome and transmute trauma. Themes of mortality are explored and revisited throughout, knowing that beauty can only be seen by knowing the sadness of its polar opposite, allowing us to understand both highs and lows as forever tied into life’s journey. Her work speaks lovingly, even if with fearless candor, acknowledging that with awareness comes burdens.

After careful preparations for the show, we were at the point of installing the mini-exhibition just one day prior to the event’s opening night, when it was decided at the last minute to include Sharrow’s large-scale work Involute. This decision proved to be a great opportunity to spend time with this piece. I was familiar enough with the painting to recognize it as an important work: it was one I chose when I served as co-curator for the 2016 exhibit Sheba Sharrow – Balancing Act at Monmouth University. However, living with it up close during my days at the art fair allowed it to resonate and speak to me as I shared its stories and explored its meaning with all who visited me wanting to discuss interpretations. Visitors were drawn into the booth space by the work itself. My job was to assist and decipher its meanings. I discovered so much about what I was seeing in the process of conversation.

Sharrow’s works can be categorized as abstract expressionist, but also engage intellectually, thematically, as works of humanist philosophy. The painting Involute, a mixed media painting on Arches paper created in 1999 and 72 x 84 inches in size, greeted guests at the booth’s right wall, allowing them to get a first impression of it from a distance and then to inspect it closely. The first impression is its physical luminosity and the quiet, yet pointed, orchestration of the painting’s composition. The title is inscribed in the upper right. The word “involute” is defined as “involved or intricate,” “curling upon itself,” and is illustrated in the spiral of a shell. The geometry of the nautilus is referenced historically in art, architecture and mathematics as one of the golden ratios of proportion. The artist’s painting itself was a joy to see and to feel in its presence and scale, with its varied vocabulary of markings: the painting of the figure’s hand, the reverberating glow of the red that radiates from the head, and the blue from under the chin, of the central figure of a horse. Elements of collage and shimmering dark colors of browns and purples make up the physicality of this powerful animal. As part of the art’s purposefully layered paint, components were added and subtracted, making the rendered work thick and luminous and the energy created visceral.

The painting’s subject matter began revealing its content to be more serious than at first glance. Conversations began the first day with people’s reaction to the horse; viewers used words like “distraught,” that the animal was in “agony,” and that the horse was “reacting” to the figure being propelled straight toward it. I listened and realized it was the horse itself—the animal’s posture—that was the shape of a shell, bending itself backward into a curl instead of following its natural lines. As I began pointing out my own discoveries to visitors, calling attention to the collage of soldiers in the lower left and the jeep behind the horse, adding to the entire painting’s framework of war, it became clear to me that the human figure at left is man’s blindness in throwing bodies into wars, launching humans like missiles not seeing their targets.

Although as an artist, I was seduced by the paint surfaces and especially the near life-size hand clasped behind the figure’s head and rendered so masterfully, as if beckoning us to touch, it became clear to me that this wasn’t an allusion to benign hand-holding, but of what has been created by the hand of man.

Returning to the fair the next day, the painting on my mind, I began the day greeting guests, diving in on the larger meaning of this painting. In speaking, I realized that the small, collaged image of a “one way” directional arrow sign with the word “one” obscured under the paint, leaving only the word “way” shown, was the big message of the path and direction of man. It does not say “one way,” but just pointed to the way of man. The horse’s reaction is red, turning the color of love into the heat of pain. The horse, which historically has been forced into battle, also represents all of nature. The horse, in the involute of its curl, sees what is happening behind its back and feels what is in front of its eyes. For me, it came as an epiphany: Involute is a painting about Man vs. Nature.

I type this to recall the fair day interpretations so as to not forget what the experience taught me. The earth is our Mother, in an infinite turning, an infinite involute. The word “Mother” applies for me as the artist, Sheba Sharrow, is a woman. As much as I do believe that an artist’s gender is not important, I take this lesson in, taught to us in painting, with the protective, kind, fierceness and empathetic love that is missing in the telling of art history of the 20th century, what was predominantly a man’s (art) world.

As with many of Sharrow’s paintings, the larger the subject matter, the more beautiful her painted surfaces are—as if she were trying to strike a balance. For me, that is what makes the artist’s work one that connects; for even in darkness, beauty wins for all who choose to see. It was no accident that, in Involute, the man’s eyes are closed and yet the horse’s eyes are open wide; it is part of nature’s larger picture with no understanding of her destruction.

I was grateful for my days at the fair, which allowed me to chat with guests about the exhibited paintings in this solo artist presentation, spurring the interesting and deeper conversations that belong to the representation of an artist’s work. I was reminded of the art critic Sister Wendy Beckett, who talked often about what it means to be in the company of greatness with such works: You become better by simply being in the presence and feeling part of something larger and greater. It puts your daily worries and upsets into a truer perspective, allowing you to better cope with life’s journey.

As I celebrate my gallery’s 25th year in 2021, I am grateful, too, to be curating collections that focus on works that other artists recognize as “great” and that intellectually engage beyond their inherent beauty. There needs to be a narrowing of the chasm of what great art looks like in museums and what people think art for the home should look like. Living with fine art can share stories, strengthen our resolve, remind us of our truths. Truly, the greatness of art collecting is to create true homes of sanctuary and allow the healing of people both individually and in our collective spirit.

I extend a special thank you to all who chatted with me at the fair as I previewed Sheba Sharrow’s art as part of my gallery’s current exhibit, “THE HUMANIST SHOW – Miriam Beerman, Jacob Landau and Sheba Sharrow,” now on view through December 18, 2021 at my Holmdel, N.J., gallery. I invite you all back to my gallery home to come chat again.

THE NEW YORK TIMES ART REVIEW; Introspection And a Warning About Brutality (Published 2002)SELECTED ESSAYS INCLUDING ART IN AMERICA 1989 REVIEW